POLET workshop on fossil fuel decline

POLET researchers and partners invite you to an online workshop to share and discuss the findings of the Contractions project identifying historic precedents and current pledges for fossil fuel decline.

Can we predict the future growth of renewables based on past trends?

The IEA’s latest World Energy Outlook refreshes sophisticated scenarios that project the future growth of solar PV. Here, I investigate if we can match their predictions by fitting an S-curve to historical growth data.

Global growth of wind needs to be double as fast as recent growth in Germany to meet IEA’s Net Zero by 2050

The IEA Net Zero 2050 Roadmap envisions adding 310 GW of onshore wind in 2030. This is the same as was added globally in the last five years. Has such a rate been ever achieved in any country?

PhD position at Lund University

New PhD position on feasible energy transitions in Sweden and Northern Europe based at Lund University. Apply by June 6th, 2021

PhD position at Chalmers University of Technology

New PhD position analyzing climate targets and energy choices in different countries based at Chalmers University. Apply by May 21st.

Can UK eliminate emissions from residential heating by deploying heat pumps as fast as Finland?

Replacing gas heating with heat pumps would reduce 90% of UK’s direct greenhouse gas emissions from the residential sector. Here we look at whether such a replacement would be feasible if the UK would adopt heat pumps as fast as one of the leaders in this technology, Finland.

Towards a post-oil Alberta

Alberta has the third largest oil reserves in the world, after Saudi Arabia and Venezuela. In early 2015, profits from the oil sands made up about 5% of Canada’s GDP Canada’s highest incomes are found in the heart of oil-sand-country. However, Alberta’s real GDP contracted over 3.5% each in the years 2015 and 2016 due to the fall of oil prices. What does this experience tell us about contractions expected as a result of decarbonisation?

Early history of wind power in Germany and the UK

Before its fast expansion in the 2000s, wind power in the UK developed slower than in Germany. Why did this lag occur? While many early studies argued that it was due to a wrong selection of policy instruments, more careful look suggest that other factors may have played a role.

Norwegian-funded research focuses on the dark side of energy transitions

Energy transitions involve not only expanding wind, solar and other low-carbon technologies but also phasing out existing carbon-intensive sources such as coal. Introducing new energy sources is often easier to advocate as it involves no job or revenue losses. However, phasing out existing energy technologies is harder both economically and politically, though it is precisely what eventually reduces greenhouse gas emissions. In a new project, we focus at this unexplored dark side of energy transitions.

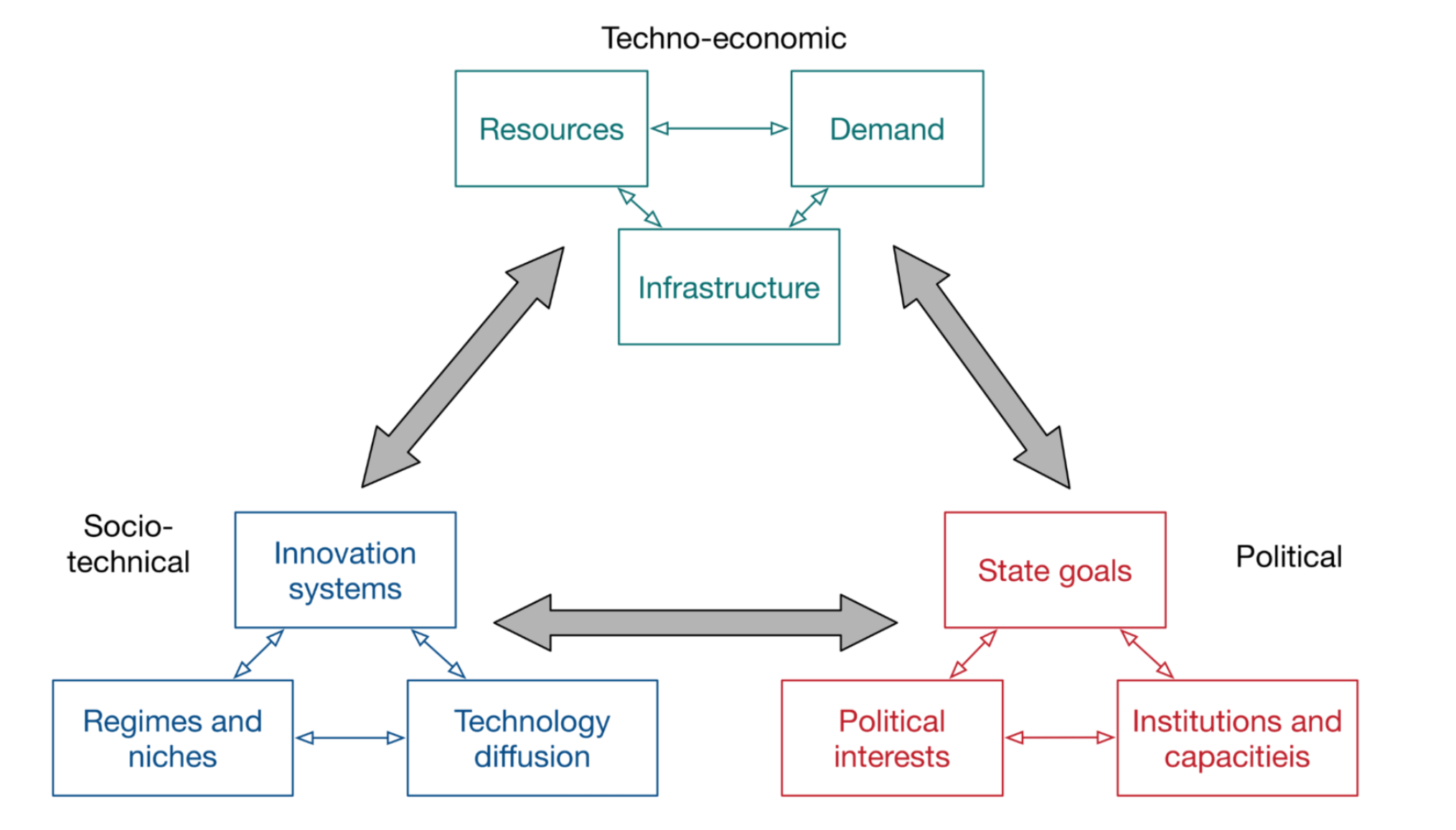

Integrating techno-economic, socio-technical and political perspectives on energy transitions

A newly published paper proposes a meta-theoretical framework integrating techno-economic, socio-technical and political perspectives on national energy transitions. The use of the framework is illustrated by a comparative analysis of energy transitions in Germany and Japan.

Does wind power grow faster in Germany or the UK?

In 2001-2014, wind power in the UK followed exactly the same trajectory as wind power in Germany in 1994-2007. Both paths are accurately predicted by the technology diffusion theory and do not show differences that would require additional socio-political explanations. What does require explanation is why the exponential growth of wind power was triggered in Germany and not in the UK in the early- or mid-1990s.

Comparing energy transitions in Germany and Japan

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua. At quis risus sed vulputate odio. Maecenas accumsan lacus vel facilisis volutpat.

Fukushima’s impact on energy in Japan should be viewed in a broader context

In response to our Comment in Nature (1), Cherp and Jewell write that Japan's ambition for renewables was not altered by the Fukushima disaster (2). Although the evidence they present is technically accurate and their point on the decreased role of nuclear is correct, we would like to bring a broader context to the readers’ attention.

Russian nuclear industry and wind power

According to an article in Kommersant, a Russian business daily, Rosatom, the Russian state-owned corporation specialising in manufacturing of nuclear equipment and construction of nuclear plants is on the way to dominate Russian wind power market.

Renewables targeted before Fukushima

In a recent letter to Nature we argue that Japan had become a world's leader in solar energy long before Fukushima. This is both good and bad news for low-carbon energy transitions. On the one hand, there is no need to wait for a nuclear disaster to develop renewable electricity. On the other hand, solar and wind energy will not magically emerge after an earthquake and a tsunami strike a nuclear power plant.